By now it should be pretty clear that learning about the Jewishness of Jesus has impacted my walk with the Lord in positive ways. One of the first books I read on this journey was Sitting at the Feet of Rabbi Jesus by Lois Tverberg.

I’ve recently had the privilege of being part of the launch team for her latest offering–Reading the Bible with Rabbi Jesus.

I’m posting an interview with Lois about the writing of this book and her interest in learning to put the sayings of Jesus back into their cultural context. The interview questions aren’t all mine. (Only one.) They’re the work of other members of the launch team. The cool thing about that is Lois answers questions I would have never thought of.

Please enjoy and learn from this terrific interview with Lois Tverberg. (Here’s a gorgeous picture of Lois too.)

You’ve written a couple of other books before this one that have similar titles – Sitting at the Feet of Rabbi Jesus and Walking in the Dust of Rabbi Jesus. How do they relate to your new book?

Sitting at the Feet was about the Jewish customs that deepen our understanding of Jesus’ life and ministry, like the biblical feasts, the Jewish prayers, and the relationship of rabbi and disciple. Walking in the Dust was about the Jewish context of Jesus’ teachings. Many of the things he said make much more sense when you know the conversation that was going on around him. Disciples are supposed to “walk in the ways” of their rabbi and obey his teaching. So I chose some of Jesus’ teachings that are especially practical for our lives and have a Jewish context that sheds light on their meaning.

My newest book, Reading the Bible with Rabbi Jesus, pulls back a bit and starts by looking at cultural issues that get in the way as we read the Bible in the modern, Western world. Among the things I asked myself as I wrote were, what cultural tools can I give readers to read the Bible more authentically? How does a lack of grasp of Jesus as a Jewish Middle Easterner cause us to misunderstand his words? Ultimately, my goal was to equip the average Christian to read the Bible more like first-century disciple.

In your new book you talk about cultural differences that get in the way of understanding the Bible and suggest that we need to grasp how the Bible “thinks.” What do you mean by that?

I started the book with a story about when my five year old nephew arrived in Iowa from Atlanta for Christmas. He had never seen snow before, so he asked, “What do you do with the snow when you have to mow the lawn?” He couldn’t imagine a reality where people didn’t mow their lawns year round, so he assumed it was universal. In the same way, many of our problems with the Bible come from misunderstanding its cultural reality and projecting our own onto it instead. We need to grasp how the Bible “thinks” – the basic background assumptions that biblical peoples had about life. Often these were very different than ours today. It’s also important that we don’t mix these two worlds together inappropriately, like mixing lawnmowers and snow.

You mention an acronym, “WEIRD,” that psychologists coined for the ways that that American culture is unusual compared to the rest of the world. How do you think this comes into play in reading the Bible?

The acronym “WEIRD” stands for “Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, Democratic.” All these traits tend to characterize Europeans and especially Americans. We live in an educated, Western culture that values scientific thought above all else. We are industrialized, so that our world does not revolve around family and clan, but around work and business. We are relatively rich, so that many basic worries are simply not on our radar screens. We live in a democracy and dislike all hierarchy and authority.

I point out that these same characteristics tend to set us apart culturally from the Bible, so that major biblical themes, like farming and kings, simply do not resonate. I explore these and other cultural difficulties that modern readers (especially Americans) have with the Bible.

There’s a chapter titled “Greek Brain, Hebrew Brain” where you discuss the difference between Western vs. Eastern thought. How does this influence how we read the Bible?

Western thinking is very analytical, theoretical and focused on abstract concepts. It began in Greece in the 5th century AD and has deeply affected European-based cultures. We see it as the essence of mental sophistication and have a hard time imagining that anyone could think any other way. Much of the Bible, however, communicates in a more ancient way. It speaks in concrete images and parables rather than abstract concepts and argumentation. In this chapter, I show that brilliant ideas can be expressed this way too, and to give readers some basic skills to bridge the gap between East and West.

Another chapter is called, “Why Jesus Needs those Boring ‘Begats.’” In it you point out that many people wonder why the Bible contains so many meaningless lists of names. What is significant about genealogies, culturally? Why were they included?

In the Bible, family was central. Even if you don’t agree with it on every issue, you have to grasp how it “thinks” in terms of family as the center of reality in order to follow its most basic themes. The growth and relationships of a family were the core of how societies functioned. The main theme of the biblical story is God’s promise to Abraham to give him a great family, and the covenant that God makes with that family, Israel. Every time genealogies are listed it shows how God is fulfilling his promise. Even in the New Testament, whether or not believers in Christ needed to be “sons of Abraham” (Torah-observant Jews, who lived by the family covenant) was a major issue.

How does our perspective change if we read the Bible as a “we” instead of merely as an individual?

Americans are very individualistic, and we tend to focus on the Bible as a series of personal encounters between individuals and God. We also assume that the ultimate audience for Bible reading is “me.” We miss how often the Scriptures focus on the group rather than the individual. When Jesus preaches, he’s almost always addressing a crowd. When Paul tells his audience that they are a temple of God, we hear it as about how “my body is a temple.” But Paul is actually talking about them all together as God’s temple, not to each of them individually. In this chapter I point out many places where things make more sense when you see them in light of their communal implications.

Here’s another example of how “we” is important. People talk about Jesus is “my personal savior” and struggle to find the gospel in the Gospels. That’s because the biblical imagery is actually about Christ saving a group of people. Jesus is the “Christ,” God’s anointed king, who has come to redeem a people to be his kingdom. When we “accept Christ” we are submitting to his kingship and joining his people. The imagery of a “kingdom” is inherently plural, so it passes right by us.

You tell about a Christian scholar who theorized that Paul knew his Scriptures by memory. Christian scholars were very skeptical, but Jewish scholars strongly agreed with him. Why was this story important to you?

When I first started hearing about Jesus’ Jewish context, I was skeptical about whether it could be of use to Christians. I was also skeptical of ideas like that Jesus and Paul likely knew their Scriptures (our Old Testament) by heart and expected their listeners to be very familiar with them too. I was told that they would hint to it and drop in little quotes often in their teaching, and these hints were often quite important to grasping the point.

At first, I absolutely didn’t believe this. But as I studied more about traditional Judaism, I discovered that even since the first century, rabbinic sermons have been overloaded with hints, quotes and subtle links to Bible passages. Memorization has been strongly stressed. I laughed when I read about a scholar on Paul’s Jewish context who spoke about this at conferences about twenty or thirty years ago. Christian scholars would all poo-poo him and say, “highly unlikely” or “totally impossible.” The Jewish scholars in his audience, however, would all nod their heads in agreement and say, of course he did!

In the last section of the book I go into more detail about how Jewish teachers studied their Scriptures and alluded to them in preaching. Most importantly, I talk about how some of Jesus’ boldest claims to being the Messiah, the Christ who God sent as Savior, were delivered in this very subtle Jewish way. There are a lot of skeptical scholars who have said that Jesus was just a wandering wise man whose followers exalted to a divine status. But they know nothing about Jesus’ Jewish habit of hinting to his Scriptures, so they miss some of his most powerful statements about being the Son of God.

What started your interest in the Jewishness of Jesus? Was there a particular event that piqued your interest?

I was raised in a devout Christian home. I’m not Jewish and my overall interest is in understanding the reality of Jesus and the Bible, rather than Judaism per se. A little over twenty years ago I signed up for a seminar on ancient Israel and the Jewish culture of the Bible at my church, thinking it would be just some dry historical information. But all of a sudden Bible stories that were foggy and confusing became clear and deeply relevant to my life. I started hearing the words of Scripture through the ears of its ancient listeners, and it made all the difference in the world.

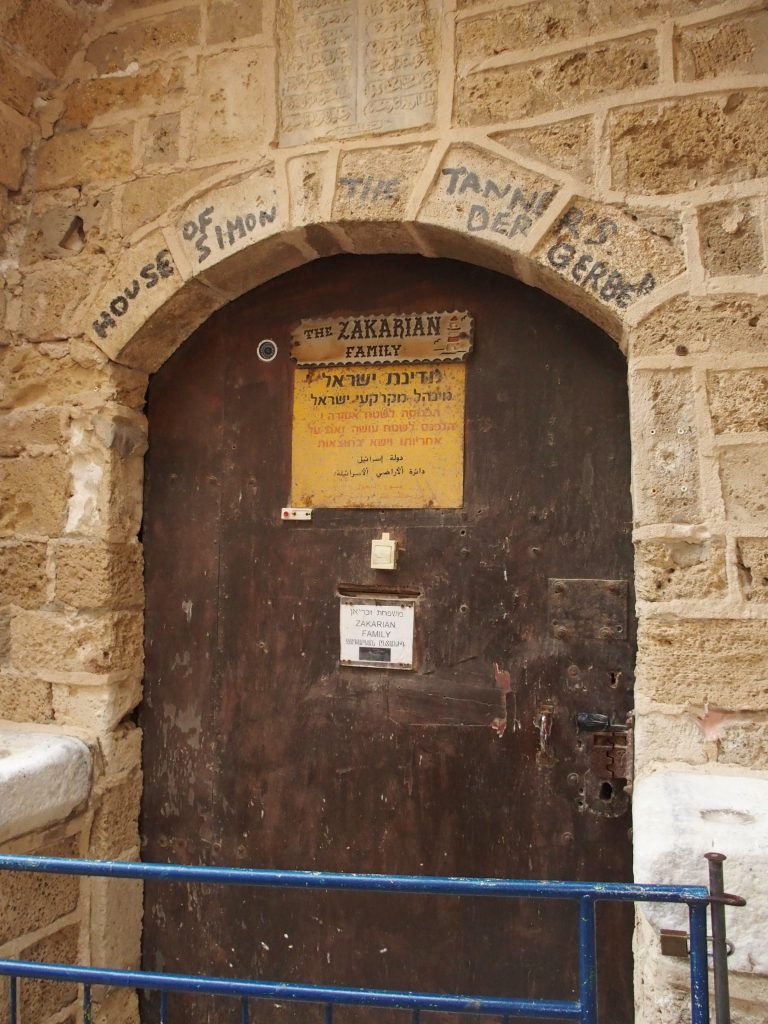

My background was originally in the sciences, and I have a Ph. D. in biology. I was teaching as a college biology professor and my background in research compelled me to dig deeper. Over the years I’ve traveled to Israel several times to experience the land and history in person and to study the language and the culture. Every time I come home I’m newly inspired, because in the past few decades scholars and archaeologists have unearthed enormous amounts of information that clarifies the Bible’s stories, particularly the Jewish setting of Jesus.

Why do you think that so many Christians are unaware of their Jewish heritage? All of the disciples were Jewish, and the New Testament was written almost entirely by Jews. But within only a couple centuries Gentiles became the majority in the church, and many were hostile to its Jewish origins. Even in Romans Paul warned the Gentiles not to be arrogant toward the Jews, but his words went unheeded. One reason was that early Christians needed to establish their identity as a new movement, and they defended their faith by focusing on their differences with Judaism. Through the ages there has been occasional interest by Christians in understanding their Jewish roots, but for much of its history the church has struggled with anti-Semitism. And Jews who had felt the persecution of Christians were understandably less than interested in helping them understand the roots of their faith. It’s only been in the last century that Christians have become avidly interested in the topic. One reason for this is because we mingle so much more. Jews and Christians now have relative freedom to discuss their beliefs, and both groups are curious about how the other reads their common Scriptures.

These excellent questions really make you want to read the book, don’t they? You can order it from any book retailer such as these:

We chose an area near the fencerow so the cool-weather plants would have adequate shade. (It also happens to be near our propane tank. Not very esthetically pleasing perhaps, but we hope it will be nutritionally pleasing.)

We chose an area near the fencerow so the cool-weather plants would have adequate shade. (It also happens to be near our propane tank. Not very esthetically pleasing perhaps, but we hope it will be nutritionally pleasing.)

I’m pro-life. Staunchly pro-life. But I find myself using words and phrases I don’t really mean.

I’m pro-life. Staunchly pro-life. But I find myself using words and phrases I don’t really mean.

This is exactly why I started writing. I was complaining one day about the library not having any good books. My then 12-year-old daughter, in exasperation, said, “Then write one!” So, I did. I like my stories. Hahaha! Good thing, huh?

This is exactly why I started writing. I was complaining one day about the library not having any good books. My then 12-year-old daughter, in exasperation, said, “Then write one!” So, I did. I like my stories. Hahaha! Good thing, huh?